Protest campaign “Stop Nuclear Waste” at Aylmer Marina

Taylor Clark

A series of multimedia exhibitions aimed to raise awareness about the Near Surface Disposal Facility project planned for Chalk River wrapped up at the Aylmer Marina on July 6.

Throughout May and June, Stop Nuclear Waste has organized these exhibits at various locations across the Ottawa Valley to showcase what was at stake with the January 9th approval of a licence for the controversial project by the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission. The decision came without free, prior, and informed consent of the Algonquin Nation, which Kebaowek First Nation argued was a clear violation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

“It’s a betrayal of a series of sacred trusts. Anishinaabe aki (land) was not created for business profit. Our Nation was not built to turn the (Kichi Sibi), our great river, into a self-storage unit for nuclear waste,” former Kebaowek First Nation councillor Verna Polson told the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission during the Near Surface Disposal Facility hearing in June 2022.

Kebaowek First Nation is among the 11 communities making up the Omamiwininiwag or the Algonquin Nation, who have spent time immemorial on the land surrounding the Kichi Sibi (Ottawa River). The First Nation was also one of four communities involved with Stop Nuclear Waste, a community movement of Indigenous leaders, local members, and allies who wish to hold the government and the Nuclear Safety Commission accountable for years of irresponsibly disposing nuclear waste.

Since its establishment in 1944, the Chalk River Laboratories has been a major research and development site that led to advancements in nuclear technology. A large share of the world’s supply of medical radioisotopes was produced at the site until the nuclear reactor was shut down in 2018. The site was also home to a handful of incidents over the years, the most recent being the discharge of toxic sewage. The incident came months after Canadian Nuclear Laboratories was awarded the licence for the Near Surface Disposal Facility.

The facility would allow the permanent disposal of solid radioactive and non-radioactive legacy waste but would require the removal of the mountainside along the river to make way for the waste disposal facility. According to an Indigenous-led assessment by Kebaowek First Nation and Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg, storing over a million cubic metres of legacy nuclear waste would directly impact the water quality, and ability of animals and plants to live along with other species in the watershed. On top of risks to the waterway, the project would also require the clearing of 37 hectares of old growth forest where Kebaowek First Nation found active traces of wildlife.

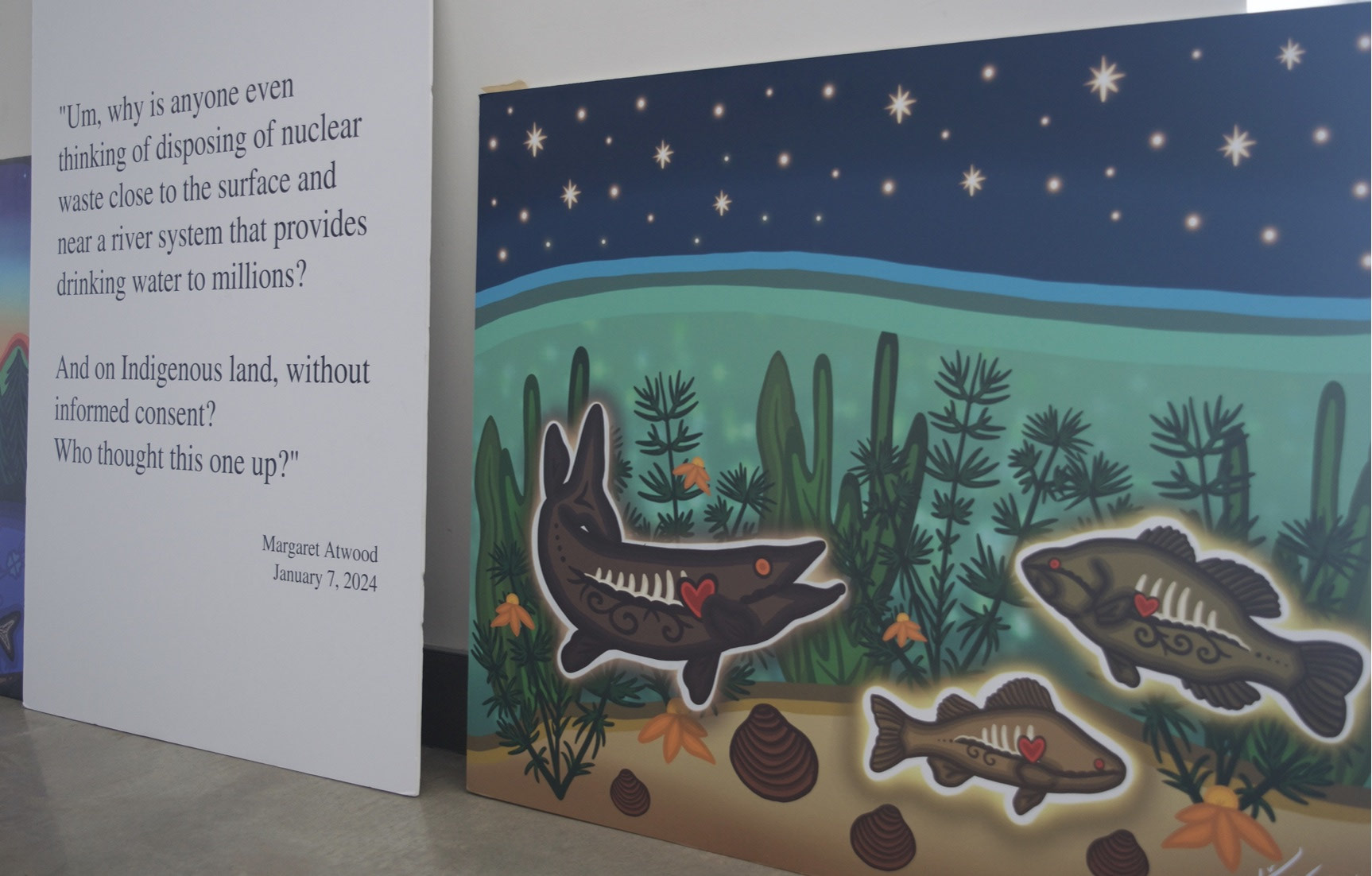

Overlooking the Ottawa River, attendees of the exhibition came face to face with images and depictions of endangered and culturally significant species like lake sturgeon, eastern wolves, and bears that would lose their habitats to the disposal site.

Kebaowek member Mary-Lou Chevrier believes she has already seen first-hand the effects of the site’s waste on the surrounding wildlife. Upon conducting a fish study in April, Chevrier was met by what she described as a metallic odour, dead aquatic animals, and “lethargic” lake sturgeons where the Petawawa River meets with the Ottawa River.

“(The sturgeons) were in about 14 inches of water and they were swimming in a circle. This is obsessive compulsive behaviour, and I was able to actually pick them up by hand out of the water,” said Chevrier.

While it was exciting to hold the ancient fish, Chevrier said the moment was also very disheartening because she had spent decades trying to reel one in.

“I think you’re privileged to be able to see one and to be able to handle them in that way, but I felt that something definitely wasn’t right,” she said.

Chevrier noted the sighting was around the time the public finally learned of the toxic sewage discharge that occurred months prior. Although there was no evidence connecting the sewage to the sturgeon’s odd behaviour, Chevrier worried about what the discharge meant for aquatic life.

“In the meantime, I had been coming across a lot of anglers who were catching and eating fish, so that really stuck with me. I felt that there should have been earlier public notification.”

The decision by the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission was challenged by Kebaowek First Nation in a judicial review in front of the Federal Court from July 10 to 11. The First Nation presented an oral argument based on both the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the United Nations Declaration Act. In the spirit of reconciliation and protecting all life, Kebaowek First Nation believed Canada was obligated to carry out free, prior, and informed consent into the consultation process as stated in Article 29.2 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples that was put into Canadian law by the passing of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act in 2021.

Those wanting to support the cause can add their name to a list of signatories demanding the Government of Canada to make no decision in terms of issuing a licence to the Canadian Nuclear Laboratories. Stop Nuclear Waste’s petition can be found online at www.stopnuclearwaste.com/petition. Contributions can also be made to Kebaowek First Nation’s legal fund by donating to https://gofund.me/7ce16728.

Photo caption: A painting by Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg artist Destiny Cole highlights the speculated relationship between lake sturgeon and hickorynut mussels, which are both included as endangered in the official Species at Risk in Ontario list.

Photo credit: Taylor Clark